A look ahead - trends that will shape shipping in 2018

Economic upswing in growth gives rise to cautious optimism among top names within the shipping industry. Policy, regulations and digitalisation will continue to impact the industry in 2018.

A holistic approach is crucial in order for the badge of “environmental friendly” to have any true meaning argues Jotun sustainability executive.

As ever greater volumes of oil and gas, soil nutrients and rare Earth metals are depleted, the world’s population is waking up to the fact that there is no such thing as a product that comes from nowhere. “At the same time, large and devastating environmental impacts, such as climate change, smog, toxicity of environmental compartments, are seen today. This shows that the effect of extraction, transport, manufacturing, and use of the products need to be reduced as much as possible,” says Anne Lill Gade, Group Sustainability Manager at Jotun.

In order for the badge of “environmentally friendly” to have any true meaning, then, products must be manufactured with ease of eventual re-use and recycling considered, and built-in, at the design stage. Introduced from a regulatory standpoint by the EU Commission in 2015, this principle is known as the “circular economy” – that of striving, as much as possible, to maintain the world’s total volume of human generated material at steady levels, rather than perpetually increasing it.

“There is no single definition of an environmentally friendly decision,” argues Gade. “The definition of environmentally friendly decisions is comprehensive and changing over time. In earlier days the focus was on content of solvents and hazardous substances.

“The definitions today are more holistic, and include the total life cycle from cradle to grave (or cradle) of the product, all environmental impacts, consumption of non-renewable resources, energy use, waste from end-of life and output flows for reuse and recycling and energy recovery and export,” adds Gade.

This approach means there are no quick-fixes or easy substitutions “Claiming that products are more environmentally friendly than others must be based on holistic overview of all impacts from all stages of a product’s life cycle and require a reduction of major impacts while not increasing others. This is much easier said than done,” points out Gade.

“The goal of a circular economy is for resources to be used in a more sustainable way,” explains Gade. “The proposed actions will contribute to ‘closing the loop’ of product lifecycles through greater recycling and re-use, and bring benefits for both the environment and the economy. The plans will extract the maximum value and use from all raw materials, products and waste, fostering energy savings and reducing Green House Gas emissions.”

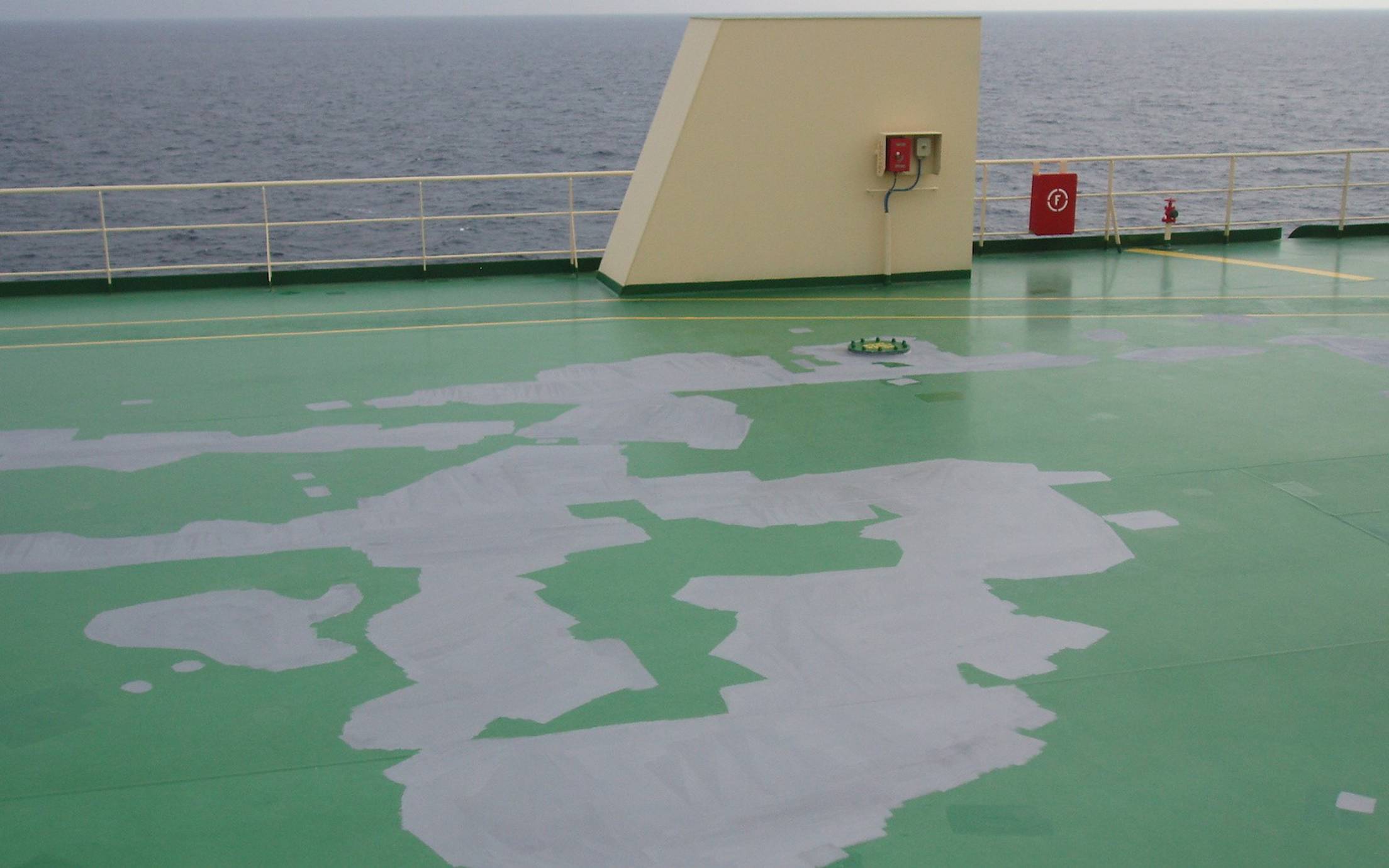

An example of this is the effect of a high quality and effective antifouling on the energy use and CO2 emission of ships. While all conventional antifouling paints polish over the course of its lifetime, quality paints are designed for as long an effective lifespan as possible. Moreover, they are intended to offset their manufacturing costs – in terms of the materials used – against the savings in the use of ship fuel, itself a valuable non-renewable resource, extracted and refined with an impact on the environment.

“In the life-cycle context the durability of the paint is decisive,” says Gade and adds, “The life-cycle assessment may also be extended to cover how the paint product may enhance the function and reduce the environmental impacts of the object that is painted. One example may be how a good new building specification can reduce the need for onboard maintenance and costly repairs in drydock. This is relevant for marine paints.”

On top of this, the company must take into consideration the effect on the environment when the ship is recycled. Vessels, in terms of their material manufacturing costs, can be highly efficient assets, since they have a lifespan of 30 years or more, and much of the steel from hulls can be recycled for other uses – where care is taken to scrap vessels responsibly. Paint’s ability to protect this steel, then, from corrosion or other forms of degradation, also contribute to the circular economy in a longer-term sense – by ensuring the long-term integrity of the material to be recycled and eventually re-used.

“The proposals under the principle of the circular economy cover the full lifecycle of products: from production and consumption to waste management and the market for secondary raw materials,” concludes Gade.

Economic upswing in growth gives rise to cautious optimism among top names within the shipping industry. Policy, regulations and digitalisation will continue to impact the industry in 2018.

Many shipping companies struggle in today’s tough markets and seek greater and greater savings. One way to achieve this is through onboard maintenance planning.

Shipping executives stress the importance of technology and innovation to drive greater sustainability in the maritime industry.

A video is being shown

An image is being displayed

A brochure is being displayed